Note: The winners for this giveaway have already been chosen. Subscribe to Tiny Buddha to receive free daily or weekly emails and to learn about future giveaways!

The Winners:

In the past decade, I have read more than my fair share of self-help books.

Though I’ve enjoyed the ones with countless action steps and workbook sheets to change my life, I’ve felt the most moved and inspired by honest, personal stories of overcoming adversity.

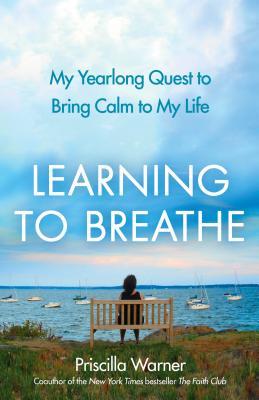

That’s how I felt in reading Priscilla Warner’s brave book, Learning to Breathe—like I was seeing straight into the heart of someone else who’d had her fair share of personal struggles, and receiving the profound gift of her experiences and insights.

Priscilla Warner struggled with debilitating anxiety for most of her life, and formerly self-medicated with vodka, before a doctor prescribed Klonopin. After four decades of overwhelming panic attacks, Priscilla adopted the mantra, “Neurotic, Heal Thyself.”

In her memoir, Learning to Breathe, Priscilla chronicles her journey through various healing modalities—including meditation, chanting, and other lesser-known alternative treatments—and offers readers hope for peace and lasting change from the inside out.

Since I hold the utmost respect and admiration for Priscilla, I’m grateful that she took the time to answer some questions about her book and offered to provide two free copies for a giveaway.

The Giveaway

To enter to win 1 of 2 free copies of Learning to Breathe:

- Leave a comment below

- Tweet: RT @tinybuddha Book GIVEAWAY & Interview: Learning to Breathe http://bit.ly/LxzDNS

If you don’t have a Twitter account, you can still enter by completing the first step. You can enter until midnight PST on Friday, June 29th.

The Interview

1. In Learning to Breathe, you chronicled your experiences exploring a wide variety of healing techniques to overcome chronic anxiety—and you shared yourself honestly and vulnerably. As a fellow writer, I’m curious: Did you experience anxiety around the process of sharing these personal experiences?

Initially, I was concerned about exposing my family members to any pain, since examining my relationships with them was part of my healing process. But I tried to write the book with as much love as I could.

I was also worried that I’d come off as self-indulgent, but all of my teachers explained that healing from my own pain would make me more compassionate to the suffering of others. I try to build that awareness all the time now.

Hearing from readers who relate to my story is humbling and inspiring. I don’t feel touched as a reader unless a writer is 100% honest, and that’s what I strive to be.

2. Early in your book you mentioned that you once hid your anxiety in shame, and self-medicated with vodka. What’s helped you most in overcoming that shame?

Knowing that I am not alone is enormously helpful. Until I wrote this book, I didn’t realize that 6 million Americans suffer from a panic disorder, 40 million from an anxiety disorder.

When I was gulping down vodka in the ladies room of my office, before a big presentation, I felt alone, broken, scared, and ashamed. When I took Klonopin before stressful events, I felt weak. Now I have a toolkit of coping skills that make me feel empowered.

The therapists, healers, and teachers I met while I wrote this book shared their own vulnerability and frailties with me, which made me feel less alone. Opening my heart to readers, and hearing their reaction to my book, comforts me in ways I never could have imagined.

3. In the beginning of Learning to Breathe, you wrote that you wanted the brain of a monk—that some people create meth labs in their basement, but you wanted to create “a Klonopin lab in your head” to naturally alleviate your anxiety. How has the relief of meditation differed from the relief of medication?

I’m very grateful that medication exists, and I still use Klonopin occasionally. But practicing meditation is much more rewarding and empowering, because I can heal from a place deep inside of me. I feel grounded, safe, and secure when I meditate.

I love knowing that my breath is my best friend, because it always ran away with me in the past, when I hyperventilated during panic attacks. I love mixing up my meditation styles. It’s a creative decision to sit with an emotion, listen to music, walk, record videos, or simply breathe quietly.

4. Early on in your practice, you learned that you might become sad, depressed, and agitated after a couple of weeks of meditating—and that this would be normal. Why does this happen when we start meditating?

I don’t really know! The monk who taught me that, Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche, is now on retreat in the Himalayas, by himself, for an indefinite period of years, so I can’t ask him!

I did hear Krishna Das caution people that building a meditation practice is like working with explosives. “You have to go slowly,” he said, “Or else boom!”

I think that when our brains are at rest we receive information we might otherwise push away or ignore. Past experiences and painful thoughts enter the picture when our minds are clearer, so that can be very upsetting. We have to be careful when noticing new emotions surrounding those thoughts.

5. You also tried Somatic Experiencing therapy and worked with an EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) therapist. Which of the different treatments you tried had the most profound effect on you, and why?

With Somatic Experiencing, I sat on a therapist’s couch, learned how to ground myself, and then slowly called to mind stressful situations, moving back and forth, in my body and mind, between feeling grounded and frightened.

I could feel my body tingling as it released nervous energy and grew stronger. I slowed down the physical reactions to stress that used to terrify me.

Traumatic events often get frozen in our primitive brain. I had discussed many of those events previously, with friends and therapists, but hadn’t processed the physical sensations they stirred up deep inside me.

All the talking in the world was no substitute for feeling the pain lodged there. EMDR bilaterally stimulates the left and right sides of the brain, and releases the frozen memories, which get reprocessed.

I felt what I already knew on a deeper, more profound level when I did EMDR therapy. And once those difficult emotions and memories passed through me physically, they no longer held me in their grip.

6. When you spoke with a neurologist, he surprised you by referring to you as a trauma survivor. I suspect a lot of us who have traumas in our pasts might have that same response. Can you expand on what you learned about what constitutes trauma?

An emergency tracheotomy saved my life when I was a child. I learned how I’d buried the memory—yet stored it in my body—in the course of writing this book.

We all suffer experiences that make our hearts stop, pump faster, and feel broken. What one person considers traumatic is exciting for someone else. I learned not to judge what constitutes trauma.

An argument with a loved one, abusive behavior, war, financial stress—unfortunately there are countless ways to become traumatized. We have to acknowledge the pain, respect it, feel it, and process it in order to heal.

7. At one point you wrote that your panic had been with you for forever, and you couldn’t imagine letting go of it. Why did a part of you want to hold onto it, and what helped you overcome that?

Panic had become my exotic excuse for being unhappy. It also, oddly, made me feel very alive. It was a great distraction from the underlying sadness I’d felt as a child, for many reasons.

I became so busy worrying about panic attacks that I didn’t have to process or understand the pain I felt growing up in a family with a lot of mental illness.

When I healed, I felt more and more estranged from my past and the people I grew up loving. It’s sometimes painful to change and leave people behind. But ultimately I accepted my new, happier self, and became grateful for the calm that makes me a much healthier person on many levels—physical, spiritual and emotional.

8. When recounting your experience at a three-day retreat with Sharon Salzberg and Sylvia Boorstein, you wrote, “Perhaps my panic could become a friend, too, or at least a nodding acquaintance.” Have you made friends with your panic, and in what way?

When I heard Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche say that the panic he’d suffered as a child was his greatest teacher, I thought “He’s a monk. I’ll never feel that way.” But now I’m grateful for the condition I had, which led me to seek peace and find it.

We can’t choose the family we’re born into, or many of the circumstances we encounter in life, but we can choose how we relate to those circumstances, how we look at them and learn from them.

I’m sorry for the pain my body and brain have been through, but I am trying to treat myself with kindness and love now. Compassion is a practice I am happy to keep learning.

9. At the end of Learning to Breathe, you talked about the results of your MRI—and how you had tangible proof of your mental transformation. For readers who also want the brain of a monk—but might not have access to a brain scan—what are some signs that they are indeed making progress?

The Dalai Lama says that after a few weeks of meditation, we begin to “live with a sense of tranquil abiding.” I love that! Everything about me, including my speech pattern, slows down after I meditate.

My husband noticed that my temper is gone, for the most part. My meditation practice allows me to build a tiny observation deck outside of myself, where I can wait a beat before responding to the world.

Dr. Marcia Lucas, a psychologist, described perfectly what I’ve come to feel:

“When you practice mindfulness meditation, your brain gets better at making sense of incoming emotional information without jumping to conclusions, reacting out of old habits, or getting stuck in emotional dead-ends like worry or grudges. It does the right stuff with that information, helping you to wisely tell the difference between what’s happening in the moment and what’s your ‘old stuff.’”

10. What is your main message for other people who struggle with chronic anxiety?

Don’t be hard on yourself. Know that the world is full of people eager to help you get well and stay well. Know that life has ups and downs that we cannot control.

I love the words of Joseph Goldstein, a Buddhist teacher: “You can’t stop the waves, but you can learn to surf.” I’m a surfer now. Waves knock me down occasionally, but I’ve learned skills that keep me from drowning.

Learn more about Learning to Breathe on Amazon.

FTC Disclosure: I receive complimentary books for reviews and interviews on tinybuddha.com, but I am not compensated for writing or obligated to write anything specific. I am an Amazon affiliate, meaning I earn a percentage of all books purchased through the links I provide on this site.

About Lori Deschene

Lori Deschene is the founder of Tiny Buddha. She started the site after struggling with depression, bulimia, c-PTSD, and toxic shame so she could recycle her former pain into something useful and inspire others to do the same. You can find her books, including Tiny Buddha’s Gratitude Journal and Tiny Buddha’s Worry Journal, here and learn more about her eCourse, Recreate Your Life Story, if you’re ready to transform your life and become the person you want to be.

- Web |

- More Posts

Though I run this site, it is not mine. It's ours. It's not about me. It's about us. Your stories and your wisdom are just as meaningful as mine.

Though I run this site, it is not mine. It's ours. It's not about me. It's about us. Your stories and your wisdom are just as meaningful as mine.

I need this book!

This book sounds amazing and I would love to own a copy. Anxiety is something that has been with me since I was very young, and I’m ready to manage it. I’m hoping this book will help inspire me to be happier.

Would love to win a copy of the book! Thanks for the opportunity.

Cool! Creative Concept and Thrilling Interview!

this sounds like a wonderful and insightful book

What a wonderful interview. Thank you! x

How beautiful touching! I would totally read this book as I feel inspired just after reading the interview! Thanks for the chance to win the book! 🙂

“oddly, made me feel very alive.” A fine interview and I can relate to her talking about anxiety making one feel alive… Thanks for sharing

would be an interesting read !

Sounds like just what I need!

Your post struck such a strong note in me. I’ve been approaching and

resisting many of the techniques that you mentioned in your blog post.

Just in the past few weeks I’ve experienced days where I could

actually breathe freely and in a relaxed manner. What a relief that

there is possibility for change. I’d like to apply for your offer of

one of the copies of Learning to Breathe.

Thank you very much,

Trish

I didn’t want the interview to end! I loved this:

“I was also worried that I’d come off as self-indulgent, but all of my teachers explained that healing from my own pain would make me more compassionate to the suffering of others. I try to build that awareness all the time now.”

It’s hard to understand that compassion starts with the self…an equally scary and comforting thought for me. My biggest struggle is probably giving myself the credit I deserve; I’ve been known to slip into self-hatred, self-destruction…and think in limiting ways about my abilities. So to know that changing the way I relate to myself will only build me into a more compassionate individual with the world…well. I guess I know where my focus should be; I guess I needn’t feel guilty about focusing on myself. Lessons, lessons, lessons. Oh how jumbled and confusing you can be; oh how helpful and surprising and rewarding, too.

“You can’t stop the waves, but you can learn to surf.” <– new mantra! This seems amazing, but would rlly love to win this book so I can give it to a friend who is rlly suffering from some debilitating anxiety right now…

I’ve been struggling with anxiety for years now, and am looking for a way to find balance again. This book would go along nicely with the naturopathic treatment I’m getting.

I always get so much out of these. Thanks! Would love to win the book because I need to get calm!!

Forever trying to learn how to breathe. This book would benefit me greatly. Thanks for the interview!

Can’t wait to read this book!

Learning To Breath looks like an excellent book and I look forward to reading it … would love to win it and refer clients to it. Thank you for your work!

The subject matter ties in with the journey I am on at this time. I am looking forward to reading this book – Thank you.

Looks like a fantastic read and a timely one for me! I would love to win a copy! Thank you for sharing!

Sounds like an excellent book and I would love to read it!

Wow, thank you for this! As an anxiety sufferer myself, I really relate to what you have said here and hope to read your book very soon!

Thank you, sounds like a great summer read.

I’m looking forward to reading this book. Thank you for bringing it to my attention. One of the most difficult things for people new to a path of self healing hears from me is that they need to try lots of things; that they will grow from each one, and probably outgrow each one at some point. They become so frustrated when they can’t find the quick fix, the one practitioner to solve everthing for them. I try to encourage them to follow their instincts and try what comes up next.

Perfect reminder for me, coming at the perfect time.

I receive and read Tiny Buddha ever day and love it. Thank you so much for your inspirational words of wisdom. I hope I win one of the books.

Yes, I did enjoy this post. I always welcome others experiences and what they did to work through them. It can be such hard work yet sooooooooo worth it when you get to the other side of it. I have tried different modalities myself and am always open to learning about any that I haven’t tried or haven’t heard of. Forever evolving!!!!!!!!!! 🙂

Pat

Panic as a friend. It’s a brave idea…SB

I have also tried many different therapies to deal with my anxiety/depression, Crohn’s disease and fibromyalgia. After 40 years I finally figured out that it’s easier to embrace the hardships and work with them rather than fighting against them all of the time. Thank you for writing about your experiences. I believe they will be helpful to many anxiety sufferers who feel there is no way out.

Thank you for this. I just started to try to meditate ad I found the part of feeling sad coming up out of the practice when

You started. I’ll have to be

Mindful of this ow. Thank u!

Interesting insight on medication. I have never quite heard “I’m sorry for the pain my body and brain have been through”. Definitely struck a deep chord with me, and made me realize it is real and deep and feeling emotional is ok.

Divine timing. Thank you! {{ ☼ }}

This is beautiful, Priscilla [and Lori]. Thanks so much. I, too, have been delving into pranayama and other means of recovering my breath. Fear, anxiety and anticipation have long affected my breathing, feeling like knots beneath my sternum. The realization is that I have or had been stopping my breath there. Meditation overcomes that. Medication does, as well, but the effects are too far-reaching into other areas of the body.

Fritz Perls, MD, the psychiatrist and founder of Gestalt therapy said, “Fear is excitement without the breath.” It’s a revelatory thought.

I look forward to purchasing and reading this book. Site bookmarked. Thanks again.

~ Mark

Looking forward to this book Thank you ! Breathing ,Meditation helps to calm …

Fascinating interview

How it amazes me that I always thought breathing was something my body just knew how to do to survive! I now have seen how often I hold my breath, forget to breathe, forget to pause and just be. I need this reminded that we must truly breathe to survive.

“Learning To Breath” is so needed by all people. At this time, it will be so read, over and over, in this family – until we all ‘get it’. It’s that important in today’s stressful world.

I have struggled with anxiety & depression all of my life. I have been on anti-depressants during twice and have vowed never to do so again. I tried using alcohol to make relax and have more fun in life, obviously that didn’t work. Through years of trial and error, I have come up with life plan that works for me. It incorporates, daily meditation, herbal and vitamin supplements, an SAD lamp during the winter and regular exercise.

A wonderful Q&A session. I am a writer exploring what ¨Life Review¨ is all about and how to process what we bring back for ¨review¨ and Pricilla´s comments about meditation give me lot´s of insight about meditation as a healing modality. I would love to learn more from her work. I can´t receive printed material where I live in Mexico but I can download e-books. I will check to see if available. Ron

I’m dealing with anxiety as well and trying different types of therapy! I’m so glad to have heard about Tiny Buddha from a friend and to have this post today is wonderful! Thank you for sharing!!! Mindfulness is so important and probably the hardest thing I’ve ever tried in my life! If only I were eight and learning this instead of 45! Ha! This is a wonderful reminder that I’m not the only one and there are so many resources and tools available. Thank you again!

If I get anymore calm I will be dead.

I’m intrigued, and will have to look into this book. thanks so much for sharing!

I must read this book! 🙂

I just started meditating daily again after many years of “sleeping”. Deep feelings are coming up through my breathing. Thanks for sharing your experience. Cannot wait to read your book.

I recently was in charge of our weekly prayer group & I chose breathing as our theme for the week. It really is something when you realize how such a simple act as breathing affects us in so many ways. Sometimes I forget to breathe and I am always so grateful for these reminders. Thank you for sharing your story. Someday I hope to take a really deep breath and share mine too:) Blessings to all!

Thank you for always helping us remember that Life is a glorious study of Life and self, as well as a continuous source of sumptuous rewards – small and large. <3

It’s so good to know that I am not alone. Glad I saw this.

I like Goldstein’s line about surfing through the waves too. When “drowning” is the alternative, you’ve shed some light on a huge wake-up call there.

Thank you for the interview!

~ Beautiful ♥ Love yourself and then you know how to love others ♥