“In the marketing society, we seek fulfillment but settle for abundance. Prisoners of plenty, we have the freedom to consume instead of the freedom to find our place in the world.” ~Clive Hamilton, Growth Fetish

I come from a time where passbook savings accounts were the norm.

I can recall skipping along to the bank, aged eight, with one pudgy hand enveloped in my dad’s and the other clutching a little booklet.

I’d wait my turn in line with butterflies in my belly. The teller was always so far away. But once I got to her, it was magical. She’d open a hidden drawer, extract the exact notes, and scribble the remaining balance into my passbook. Et voilà—cash in hand!

Everything about this performance was concrete and transparent: Whenever I withdrew money, I immediately saw my bank balance decline. And without the risk of it nosediving into overdraft, it’s how I understood money was a finite entity. It’s how my parents taught me to not spend beyond my means, to only buy stuff I needed or had saved up for.

Having a passbook savings account in my childhood and adolescence protected me from buying stuff carelessly.

Fast-forward to 2018, now living in Australia—which equates to residing in opulence for those living in developing nations—I’m not only thirty-six years apart from my eight-year-old self, but also thirty-six worlds away. In this world my eight-year-old self would throw a tantrum if she didn’t get the Barbie doll she wanted. I blame credit cards for that.

What also saw me come out on top all those years ago was the absence of the advertising glut that now penetrates an eight-year-old’s sphere.

In 1982 Fiji, TV did not exist. I played outside. I read Enid Blyton. I didn’t read the newspaper. And I can’t bring to mind any specific billboards of that time, even though I’m sure there were a few in the city, where I did not live.

Today, at forty-four years of age living in the era of affluenza and having a disposable income, advertisers know my attention is priceless. Yet, they get it on the cheap. This is despite my creating an anti-advertising bubble to cushion me: In 2014, I deleted my Facebook account. In 2017, my Twitter account. While I have Instagram, I do not use it. And I rarely watch commercial TV.

The ads for stuff don’t just infiltrate this bubble—they gush in. Into my inbox, even when I didn’t sign up for the next celebrity’s latest self-help book because I am something to be fixed. On my phone, when I receive a text promoting a sale of 15% off TVs all day today (and today only!). On trams, trains, buses, buildings, freeways…

The humble bus shelter does not escape from being turned into a billboard either. When I walk my dogs, I pass one that is currently telling me I can “drive away in a Polo Urban for only $16,990.” (Do I need a new car? After all my current one is nine years old, although it is running smoothly. Hmmm…) The posters on this shelter change weekly. It does not allow me the grace to become immune.

Even if I could construct an impenetrable bubble, it’d be pointless. The Internet and its cookies would see to that.

These cookies know—and remember with unfailing memory—what I desire (printed yoga leggings!). And they flaunt my desires by dangling carrots in front of me, whether I’m reading an online article, watching a video on YouTube, or searching on Google.

And if the Internet tempts with its cookies, then it decidedly seduces with its availability. I can now stare at the blue light on my ever-ready smartphone and make decisions to buy yoga leggings whenever I want.

The perfect time to do just that is before I flop into bed, after a long day’s hard work, cooking dinner, washing dishes, and watching an episode or two of my favorite show on Netflix. I should feel elated when I hit the buy button, but I find myself getting into bed not only with my husband, but also with guilt and a larger credit card debt.

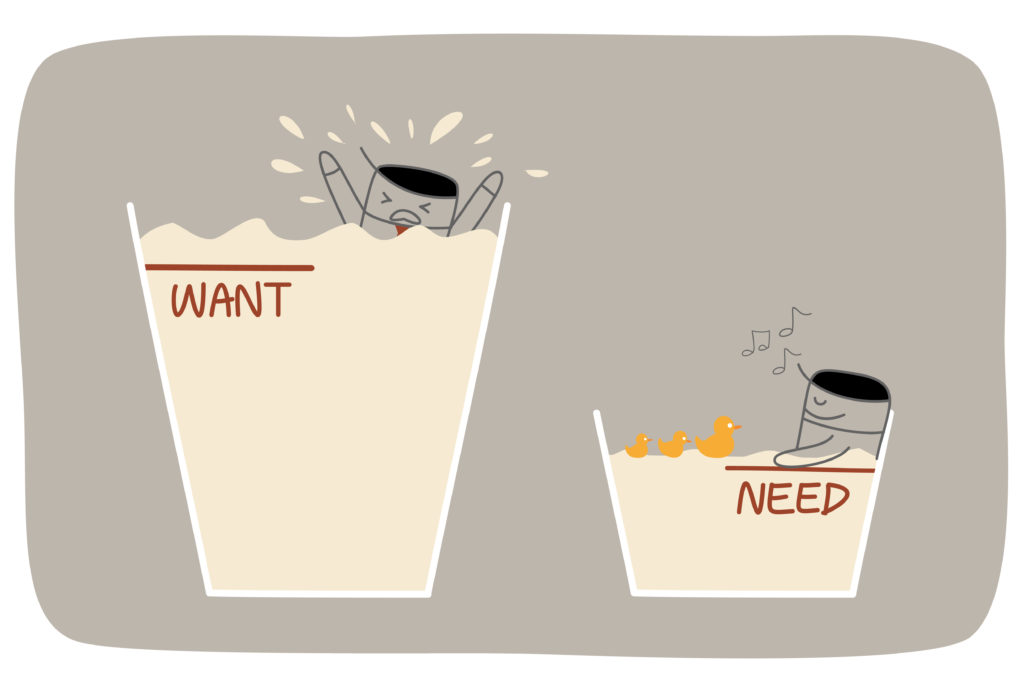

The grab for my attention and time under the guise of convenience and a better life is, however, simply the tip of the iceberg. What no one can see is that I am waging a war against myself—with the monkey-mind chatter that jumps from one justifying thought to another, convincing me that something is a need not a want. This is an example of what the Buddhists call suffering.

About two years ago, my husband and I moved into the new house we built. It’s much bigger than one we’ve ever lived in. And as we prepared to move into it months beforehand, the justifications began:

We need new furniture to match the modern feel of the house. (Danish style, as we had been subconsciously brainwashed by Instagram with everything that was hip in interior design.) And we need a bigger TV for the bigger living space. A new fridge because our old one won’t neatly slide into its allocated spot of the spacious kitchen. And more paintings, since we now have more walls…

Not only did we ‘need’ all this stuff, but we also had to choose stuff that was ‘us.’ And it all had to look ‘just so’ when put together. So we researched online. Visited furniture, home, and electrical stores each weekend. Read reviews. Let the cookies take our minds into a rabbit hole of stuff we didn’t realize we needed.

Just thinking about all the time, money, and energy we invested to get it ‘right’ sets my heart aflutter and raises a sweat. It was gruelling—the number of choices, the number of decisions (Did you know that an eight-year-old now has hundreds of different Barbie dolls to choose from?). Luckily my husband and I have similar tastes; otherwise, I’m afraid, adding a number of arguments into the mix might have broken us entirely.

The evidence continues to pile up in favor of stuff even after the purchases have been made. After decking out our new house, I soon learned that not only did I possess things, but they also possessed me.

I worried about scuffing the freshly painted walls, staining the white kitchen benchtop with turmeric while making a curry, and my nephews scratching the wooden dining table by racing their toy cars on it. (What’s that saying? Is it “Stuff is meant to be used and people loved”?)

If I didn’t feel the compulsion to fill in the space, to make everything perfect, simply because the world presents me with the choices and pressures to do so, what would—what could—I do with all that extra time and energy, not to mention money? Read, write, hang out with my mum? See another part of the world? And, more importantly, who would I be? A happier, more relaxed person? The irony.

So, with the odds stacked completely against me, how do I even stand a chance of coming out on top of all this stuff? (How does anyone?)

I don’t believe the answer is to cut up my credit cards and get a passbook savings account, or to become a Luddite. The answer lies in cultivating awareness. By becoming aware of my thoughts and feelings, I can regain my power. Asking questions is paramount:

Will it give my life meaning? Make my life easier, better? Why do I really want it? Is it only because I am chasing a feeling? Or because I want to squelch one? What would happen if I didn’t buy it?

Failing this, I can always remind myself that almost everything material is optional.

About Lesh Karan

Lesh Karan is a Melbourne-based poet and writer. Her words have appeared in Australian Poetry Journal, Brevity, Cordite Poetry Review, Island, Mascara Literary Review, and Rabbit Poetry, amongst others. Lesh’s work has also been previously shortlisted for the New Philosopher Writers’ Award. She is currently undertaking a Master of Creative Writing, Editing and Publishing at the University of Melbourne. Read Lesh’s work at leshkaran.com.

Though I run this site, it is not mine. It's ours. It's not about me. It's about us. Your stories and your wisdom are just as meaningful as mine.

Though I run this site, it is not mine. It's ours. It's not about me. It's about us. Your stories and your wisdom are just as meaningful as mine.